CO₂ storage in the subsoil: a climate protection project

A future-oriented pilot project is on the agenda in Trüllikon, Canton of Zurich: the Swiss government, under the lead of ETH Zurich, is testing whether CO2 can be safely stored underground in the former Nagra borehole. The first tests are scheduled for next year.

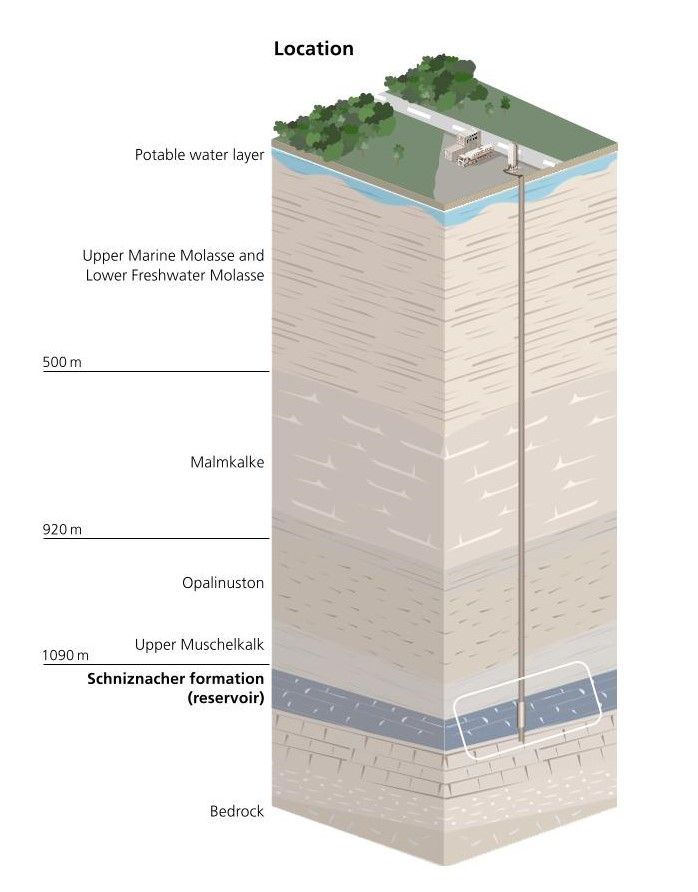

Close to Trüllikon there is a window into the geological substratum – and thus a possibility of contributing to reducing CO2 in Switzerland. A few years ago in the municipality in Zurich’s Weinland region, the National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste (Nagra) drilled a deep borehole in order to test the rock substratum for its suitability to storing radioactive material. Ultimately, Nagra proposed a different site for the deep geological repository. But the borehole near Trüllikon, which is a good 1,300 metres deep, is not being sealed for the time being. Instead of radioactive waste, the plan is to soon introduce another molecule deep into the layers of rock: CO2. The Swiss government wants to assess the feasibility of storing liquid, dense CO2 in Switzerland. In autumn 2024, the Federal Office of Topography took over the borehole from Nagra and – together with ETH Zurich, the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) and the Federal Office of Energy (SFOE) – is now planning a pilot project to examine the potential and challenges involved in injecting CO2 into the Swiss substratum.

Ideal rock deep underground

According to Herfried Madritsch, Coordinator Geoenergy at swisstopo, “this is an opportunity that Switzerland can make use of. Thanks to the preliminary work conducted by Nagra, we already have very detailed knowledge of the local geological conditions.” This preliminary work therefore does not need to be done.

Whereas Nagra primarily investigated the opalinus clay at a depth of approx. 900 metres, the focus in terms of injecting CO2 is on another, even deeper geological layer: shell limestone at a depth of 1,100 metres. This limestone and dolomite rock is a deep aquifer that extends below ground across virtually all of the Swiss Plateau. According to Madritsch, these types of saline aquifers are theoretically ideal for storing CO2. Here, the carbon dioxide, which is pumped into the ground in liquid form, is dissolved and subsequently distributed in the layer of rock. A cap rock is needed to prevent the dissolved CO2 from re-emerging at the surface. In Trüllikon there is a first geological barrier of this kind directly above the shell limestone. Above this are other cap rock layers, including the already intensively studied opalinus clay, which is deemed to be very dense.

Madritsch emphasises that the pilot project is not about testing a new procedure. It is used on a routine basis at other locations. In the USA and Canada CO2 is stored in the ground, whereas in Europe CO2 has to date been primarily stored beneath the sea. The project involves two main goals, Madritsch says: “Firstly, on a very small scale, the idea is to see how much CO2 can actually be absorbed by the shell limestone.” The injectivity, or the extent to which a gas or a liquid can be injected into the rock layer, is particularly important. The injection rate is key here. Secondly, the aim is to demonstrate that the CO2 remains below ground and does not escape. To a limited extent, the pilot project serves as a test run for the official approval process for CO2 storage. If permission is granted, the technical processes will be reviewed – from monitoring of the CO2 injection and the geological repository through to the entire process from separation to storage. In addition, the question of whether this type of facility is economically viable needs to be clarified.

We use state-of-the-art technology and sound science to investigate how CO2 storage can contribute reliably and safely to Switzerland’s climate strategy.

Taking the safe route

It remains to be seen what the next steps after the pilot project would be. Regardless of the findings, this is not a preliminary decision as to whether Switzerland will store CO2 in geological layers in future and where this could occur. Madritsch rules one thing out, however: “It’s not about building a CO2 storage facility near Trüllikon one day.” Given the local property of the shell limestone it can be assumed that the substratum in this area is not suitable for a large-scale storage of carbon dioxide. The rock is very dense and not particularly permeable, so larger quantities of CO2 can only be absorbed very slowly.

So what is planned once the pilot project is completed? “This injection test is a first step that will open other doors further down the line”, says Andreas Möri, Head of Geological Mapping at swisstopo. The pilot project serves to better explore the potential available in Switzerland. One thing is clear: there are certain CO2 emissions that will not be avoidable in future either, for example from waste incineration plants or from the cement industry. “We have to remove this CO2 from circulation in order to meet the net zero target by 2050.” Switzerland, as a landlocked country, does not have the possibility of building CO2 repositories offshore on the ocean floor, so storing it nearby would make sense. Möri emphasises that it is not yet possible to say where these CO2 repositories would be built. “We first have to conduct better investigations of the substratum.”

According to Möri, the pilot project near Trüllikon is a first step in this direction. However, it is clear that it will not be the Swiss government that will build future CO2 repositories on its own, but private stakeholders from industry and business. “With the Trüllikon pilot project, swisstopo and the other partners involved are supporting future initiatives for CO2 storage in the Swiss subsoil. We are paving a safe way for this.”

Trüllikon is taking things in its stride

It makes sense for the borehole to be used for further scientific purposes.

It goes without saying that an injection test of this type will be criticised. Opponents warn about possible safety risks such as gas leaks or earthquakes that could be caused by the pressure used to inject the CO2. But Herfried Madritsch offers some words of reassurance: the procedure has been well researched, and the risk is extremely low. Nevertheless, potential risks would be carefully investigated. Monitoring of the pilot project would serve to prove that everything is well sealed.

Questions about safety also came up in the municipality of Trüllikon. The local council collected these questions and submitted them to ETH and swisstopo, states the mayor, Claudia Gürtler. She says that the responsible persons addressed the individual points during a meeting in the municipality and provided detailed answers to the questions. Gürtler rates the exchange as very positive: “We felt that we were taken seriously and could discuss things on equal terms.” Overall, the local council takes a neutral position on the project. It makes sense for the borehole to be used for further scientific purposes.

But it will be some time yet before CO2 is pumped into the substratum in Trüllikon. At the moment, the main thing is to draw up the specific project plan, obtain permits and present a detailed cost breakdown, Madritsch says. If everything goes according to plan, the first tests could take place in mid-2026. The pilot project is expected to run until 2030.

Index

Additional content

1st Caprock Integrity & Gas Storage Symposium 2024 – Extended abstracts

The CIGSS aims at providing a platform for the exchange and discussion of scientific, technological, industrial, and regulatory advances related to the integrity of caprocks in the context of geological storage of CO2 and gas storage in general. The specialised conference is addressed to research institutes, industry, and government agencies. The event took place over two days, on 24 and 25 January 2024. The first day was devoted to a symposium with government agencies, industry representatives and invited speakers.

Folio 2025 – Per una Svizzera sicura

La sicurezza va ben oltre il campo militare. Comprende tematiche molto diverse tra loro, tra cui la prevenzione dei pericoli naturali, la gestione e lo sfruttamento sostenibile delle risorse, la garanzia della proprietà fondiaria, la stabilità delle infrastrutture e l'informazione della popolazione. In tutti questi ambiti, i geodati svolgono un ruolo chiave.